The Splendor and Glory of the Sacred Image

By Matthew J. Bellisario O.P. 2012, 2013, 2020

The par excellence of all theologians, Saint Thomas Aquinas, wrote in his explanation of the sacred image the following, “There were three reasons for the introduction of the use of visual arts in the Church: first, for the instruction of the uneducated, who are taught by them as by books; second, that the mystery of the Incarnation and the examples of the saints be more firmly impressed on our memory by being daily represented before our eyes; and third, to enkindle devotion, which is more efficaciously evoked by what is seen than by what is heard.”

In 2012 I gave a lecture at my local parish in Sarasota, Florida concerning sacred images. I received a positive response from those who attended the lecture so after some thought I decided that it may make an informative blog article. I originally posted this lecture as a series of posts on my old blog Catholic Champion in 2013, which has since been retired. There are however several essays that with some editing I think are worthy of passing over to this new blog. This is one of them. The sacred image, and the devotion that surrounds it is dear to my heart. I hope that this lengthy revised essay may increase your love of God and His Saints through an increased veneration of the sacred image.

Introduction

“And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us.” John 1:14

If we were to be transported back almost 1200 years, to the 11th of March, 843 to the glorious crown jewel of Christendom at the time, Constantinople, we would be witnessing one of the eye-catching and jubilant processions to ever be held in the city. We would see the stunning Empress Theodora, along with the Archbishop, his priests, and all the faithful chanting as they passed through the streets of the city carrying icons to the grandest of all churches in Christendom, the Byzantine church, the Hagia Sophia, known as ‘the church of Holy Wisdom’. This would be where the Eastern Church would celebrate the triumph of Orthodoxy, that is, the victory over the iconoclasts who had plagued the Church of the East for over 100 years. As the people chanted their way into Justinian’s masterpiece, anathematizing the iconoclasts, they must have recollected the many men and women who had been tortured, exiled or even murdered to defend the sacred image. Many of us remember when we attended our first Latin Mass and how excited we were to see the Latin Mass arise from the ashes after 60 years of oppression. The Byzantines must have felt much the same, yet even more appreciative of their triumph, since it was one which had overcome by the blood of their brothers, sisters, and forefathers which now stained the soil of their streets and monasteries. A Byzantine scholar writes that the heroic virtue of the Saints of this period would fill several volumes of books. Why did the Christians of Constantinople fight so vehemently to retain the use of the icon, or sacred image? Hopefully, by the end of this essay, I will have provided some answers, and also have instilled in you the reader a spirit of reintroducing the veneration of sacred images in our time.

The Problem

There are certainly several reasons why such a topic is of great importance to us as Catholics today. With the dawn of this new iconoclasm in the Church of our age, it would be of little effort to prove that a new spirit of evangelization is needed in the realm of Sacred Imagery within the Western Church. Many of our once beautiful Catholic churches built by our forefathers have been openly desacralized, and many of their Sacred Images have either been destroyed or removed from these holy places of worship. Our modern iconoclastic crisis is not limited to the destruction of the older churches, but many of our new churches were constructed under a most heinous heretical enterprise. Our modern church architecture has declined far beyond even the barren whitewashed tombs born out of the iconoclastic mindset of the pretended “Reformers” such as Calvin of the sixteenth century. The primary aim of my essay is not only to condemn the errors of the iconoclasts of our age. This essay is to be first and foremost oriented towards the love of God, His Church, and His Saints, and to hopefully inspire you to develop a devotion to Christ and His Saints through the sacred image.

The Solution

If we are to understand the important role of the sacred image in our lives as Catholics, and if we are to prudently share the one true faith with others as the Church calls us to do, we must be armed fully with faith and reason. This means that we must put an effort into learning more about our faith, and putting what we learn into practice. Benedict XIV had just cause to write: "We declare that a great number of those who are condemned to eternal punishment suffer that everlasting calamity because of ignorance of those mysteries of faith which must be known and believed in order to be numbered among the elect." So my aim is also to give you more information about our Catholic faith, so you may be enriched and then enrich others in the Catholic faith. This essay is not by any means an in-depth analysis of this most theologically and historically complex subject. I have composed this essay to hopefully give you the tools to make the sacred image your own in your parish church and in your own home. Furthermore, I hope to demonstrate that we have not only a just cause to rebel against those who seek to eradicate the use of sacred images in our Church, but it is a duty. I hope that this written presentation will inspire you to live the Catholic faith in the midst of our own persecutions. At the end of this essay, I will list the many valuable sources I have used to write this so that you may obtain them for further study if you wish. It may come as a surprise that many of the sources I used are from Eastern Orthodox scholars rather than Catholic scholars. The simple reason being is that Catholic scholarship on this subject is embarrassingly limited. I hope that this will change in the future.

It is always a good practice to meditate on the incarnation of Christ, to which the Sacred Image is so uniquely and intimately bound. It can be said that the icon is truly Christological and theological, and outside the dogmas and doctrines of the faith, they cannot be properly understood. Metropolitan Hilarion, the chairman of the Moscow Patriarchate’s Department for External Church Relations, and who is also one of the most relevant modern scholars concerning the icon, in his Feb 5th, 2011 lecture on the meaning of icons said, “The icon is closely bound up with dogma and is unthinkable outside its dogmatic context. Through artistic means, the icon communicates the essential doctrines of Christianity of the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation, salvation and human deification.” This is an important fact to keep in mind as you go through this essay. Sacred images, or icons as I will also refer to them throughout this paper, are not like any other art in the world, being that they are uniquely Christian, created not only to teach the Christian faith but to lead us more fully into living the Christian faith. They are more than depictions of past events, portraits, or mere decorations designed for our churches. The icons are windows or doorways to the eternal. They are the gospel of Jesus Christ in image.

Early History and Archeological Evidence

Our journey in tracing the use of the sacred image first leads us to the catacombs just outside of Rome. Here we have some of the earliest depictions of Christ frescoed on the walls underground where Christians had Masses for the dead who were buried there. The images of ‘Christ and the Samaritan Women’ and ‘Christ the Good Shepherd’ date back to the early third century. The image of Christ the Good Shepherd from the catacombs of St. Callixtus brings to mind the Gospel of John 10:14-15, “I am the good shepherd; and I know mine, and mine know me. As the Father knoweth me, and I know the Father: and I lay down my life for my sheep.” These images and others from the catacombs were once thought to be the only Christian images to exist from this period.

The excavations from the house church in Dura-Europos on the Euphrates, however, would change all of that. This archaeological treasure would now prove that the early Christians used sacred images in their regular liturgical functions. The Dura excavations of 1932 with the discovery of the Christian house chapel and its astounding wall paintings not only proved to be a pleasant surprise to Christian iconophiles but also to the Jewish religious scholars who were completely astonished to also find a buried synagogue covered interiorly by iconic depictions of the Old Testament. This unearthing event brought new light to Jewish scholars who previously believed that images had no place in Jewish worship. It is also interesting to note that the Jewish mural paintings are for the most part void of movement, a core characteristic of the Christian sacred image. We will talk more about this later in this paper.

The Dura excavation disproves two common theories that modern iconoclasts often pose against the use of images in the Christian Church. The first being that there were no public places of worship in the early Church that used images, and that the use of images cam from the infiltration of Roman pagan practice. We can firmly state, based on the opinions of archaeological scholars, that the Dura house church was not a prototype of the Christian image, but an example of a Christian practice already well established. A scholar commenting on the Dura site as it was being excavated wrote, “We are not dealing with prototypes, but with types that are already firmly fixed. How much earlier than 200 A.D. these iconographical forms were first invented, where, and by whom, we are not yet ready to say. But this much, at least, is certain, as the study of the iconography indicates, the tradition has nothing to do with Rome.”

Being that we have images firmly established in the Roman catacombs and in the Syrian desert both in the early to mid-third century indicates that the use of images was more than an isolated practice in the Church, confined to underground burial chambers. Newer archaeological excavations are also increasing our knowledge base of early Christian imagery. For example, the new excavations in the catacombs of St. Thecla near Rome have now revealed late 4th century images of the apostles.

Iconographical Development

The icon or sacred image, developed in the same way that dogma and doctrine developed in the Church. Just as the Church’s theology advanced in-depth and understanding in the first centuries of the Church, the design of the icon also developed and advanced. Through the Church’s Ecumenical Councils, of which the first seven were primarily of a Christological nature, the Church did not invent new teachings but concretized and developed those which had already been passed down from Christ and His apostles. This development of theology and sacred image are inseparable. The iconographic theologian Leonid Ouspensky writes, “In all its fullness, (the icon) has been inherent in the Church from the very first, but, like other aspects of its teaching, it becomes affirmed gradually, in response to the needs of the moment, as for instance in... reply to heresies and errors, as in the iconoclastic period.” It was the Seventh Ecumenical Council of 787 that eventually brought upon the repose of the iconoclastic controversy of the eighth century.

Certainly, controversy was present in the early Church concerning the use of images, this we cannot deny. The early Church had good reason to be cautious about the use of images for fear that the idol worship of the pagans would infiltrate the Church. I believe that this is the main reason we do not see the use of statues earlier on in liturgical worship. Statues were readily identified more closely with pagan idols and therefore were not introduced until much later, and primarily in the Western Church.

The technique used to paint these early sacred images were obviously borrowed from earlier Persian, Egyptian, Roman, and Greek secular imagery. Like many things, the Church has always had a unique way of cleansing and elevating secular practices, making them uniquely Christian, and the use of images would be no exception. We can see a similarity of secular Egyptian funerary paintings to the earliest Christian images. However, Byzantine art scholars seem to unanimously state that the Christians, although borrowing artistic ideas from their secular ancestors, created a unique Christian art paradigm that would, in essence, demonstrate a reversal of the role of images from that of their pagan ancestors. The material world would now become of secondary importance to the eternal spiritual world. For the Christian the spiritual world was not some far off journey across the river of Styx as it was for the Egyptians, it was a very clear and present reality for them. For the Christian, the sacred image was a direct reminder of the corporeal integrating with the eternal.

The harsh persecution against the early Christians made the widespread and open use of images difficult, and many were probably destroyed under such persecutions. This is certainly one reason we do not have earlier archaeological evidence than the early third century. The persecutions made the symbolic images such as the fish, the cross, the sailing ship, the lamb, or the palm expedient to use, being that they were not explicit enough to attract attention. Yet, the images such as that of the fish were invented to convey certain truths of the faith, yet hidden to the untrained eye. We must recognize that after the rise of Constantine and his Edict of Milan in 313, that many small older house churches were most likely destroyed and replaced with larger churches. The edict which allowed the free practice of Christianity in the Roman Empire made the house church obsolete, and any that may have had images have probably been long-buried or destroyed, as the Dura Church. What early evidence we do have however demonstrates that the early Church used images in her places of worship. This evidence also gives us good reason to think that the Church authorities of the era also approved of their use, since they would have been present at the liturgical functions which took place at these sites.

The universal Tradition among all of the apostolic, historical Churches, including not only the Eastern and Western Catholic Churches but also the Eastern Orthodox and Coptic Churches, etc. all retain the use of the sacred image. The Church Fathers of the 4th century such as Saint Gregory of Nyssa firmly substantiate the use of images as one rooted in apostolic tradition and readily present in the larger churches of his age. Saint Gregory describes one of these churches with great enthusiasm, “When a man comes to a place like the one we are gathered here today, ... he is at once inspired by the magnificence of the spectacle, seeing as he does, a building splendidly wrought with regard to size and the beauty of its adornment, as befits God’s temple,...The painter too has spread out the blooms of his art, having depicted on an image the martyr’s brave deeds, his resistance, his torments...” In Saint Gregory’s time, the mid-fourth century, the Church had begun a new phase of large basilica type churches that utilized fresco and mosaic mediums in iconography. The iconography from some of the churches of the mid-fourth century in Italy and Greece gives us examples of what Saint Gregory was speaking about. Iconographic examples include the chapel of San Aquilino in Milan and the Hagios Giorgios in Salonika. These mosaic and frescoed images became the standard medium of the icon until the turn of the millennium when other mediums became more predominant.

The Iconoclastic Controversy and the Incarnation

The iconoclastic controversy of the eighth century and the Ecumenical council that followed are of the most important events of Church history, being that it not only directly addressed the use of sacred images but more importantly, it addressed the incarnation of Christ. In other words, the seventh Ecumenical Council which addressed iconoclasm was primarily Christological in nature. The event brought a waxing and waning of infighting concerning the use of sacred images to a head in the Church. Metropolitan Hilarion illustrates the importance of the Council, “The entire Christological dispute, in fact, reaches its climax with this council, which gave the icon its final ‘cosmic’ meaning… In this way the justification of icon veneration brought to a close the dogmatic dialectic of the age of the universal councils.”

The event also provides an excellent platform to discuss the Old Testament prohibition of the use of graven images, and how this Biblical text is to be understood in its proper Christian context. Deuteronomy 5:8-9 and Exodus 20:4, are the proof texts often used by heretics claiming that Catholics are guilty of idolatry by using sacred images in their liturgical and private worship. The text of Deuteronomy claims, “You shall not make for yourself a graven image, and you shall not bow down and worship them.” And the Second Commandment given to Moses in Exodus says, "Thou shalt not make to thyself a graven thing, nor the likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath" How do we reconcile this prohibition with the doctrine of the sacred image taught by the Catholic Church?

It must be noted that the prohibition is obviously not a prohibition on all images since in Exodus 25:1-22 God actually commands the Jews to make images of the cherubim on the Ark. The cherubim commanded to be depicted by God seems to directly go against the text prohibiting graven images. Likewise in Exodus 26, we see the cherubim embroidered on the linens in the tabernacle. Other Old Testament references such as that of Moses and the Bronze Serpent, a prefigurement of Christ, as well as the building of Solomon’s temple, a prefigurement of later church buildings, further demonstrate this point. The ban does not prohibit all images, but first and foremost it bans the idolatrous depictions of false gods, which would be used for false idol worship, which would be a breaking of the first commandment.

Secondly, it was not possible at the time for the Jews to depict the one true God Himself since no man had ever seen God in any corporeal sense. Hence the Jews were forbidden to depict God in the heavens above. Of course, this would all change since, through the coming of Christ, we are now able to see the Father. "I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.” (John 14:16) Saint John of Damascus, the great apologist of the sacred image, hymnographer, and defender of sacred music wrote, “Of old, God the incorporeal and uncircumscribed was never depicted. Now, however, when God is seen clothed in flesh, and conversing with men, I make an image of God whom I see. I do not worship matter, I worship the God of matter, who became matter for my sake, and deigned to inhabit matter, who worked out my salvation through matter. I will not cease from honoring that matter which works my salvation.”

It is important to understand the development of the Christian teaching of these Old Testament texts concerning the depictions of the one true God. Before Christ, God had not yet been revealed in the flesh. Once Christ took on human flesh, this obviously revealed something that had not previously been revealed to the Jews. The unique bond between Christ’s incarnation and the sacred image is most beautifully explained by two of the great Saints of the iconoclastic period, Saint Theodore the Studite and Saint John Damascene, whom I will again later quote at length. Likewise, the texts of the seventh Ecumenical Council provide more insight into the Christian understanding of the use of the sacred image. The apparent problem of reconciling the Old Testament ban lies only in misunderstanding the context of the prohibition, which ultimately depends on Christ’s incarnation, one’s ability to understand the difference between idolatrous and non-idolatrous images, and the intended use of the image. We must understand that the Christian does not worship the image, but gives veneration to the person depicted in the image, such as the Saints or the Theotokos. Worship that is given to God alone is reserved to God alone, and when for example, Christ is depicted in the icon, then we are able to give that worship which is due to God, through the icon. The icon, when properly understood, is not an end within itself but leads to the eternal reality beyond itself.

Although the history of the iconoclastic period in the East is quite complex, I will attempt to give you a simplified overview. The era between Constantine in the early 4th century and the iconoclastic period of the early 8th century is one that develops the use of the sacred image in large churches. Justinian and Theodora’s rule during the sixth century was a rich period for church iconography. It can be said that this period was the last time that East and West enjoyed a united empire, one which soon quickly unraveled. One example of this artistic development is the 6th-century church in Ravenna, San Vitale, which contains some of the most famous icons from the pre-iconoclastic period. Thankfully this jewel of Christendom remained untouched during the period of iconoclasm.

Although many influences can be cited as to the cause of the crisis, such as the rise of the Islamic heresy, the definite Jewish influence on the Byzantine Emperor, as well as political pressures, the main instigator appears to have been the Nestorian bishop, Xenaeas of Hierapolis, whose party gained influence over the Byzantine emperor Leo III. (Nestorianism teaches that the human and divine essences of Christ are separate and that there are two persons, the man Jesus Christ and the divine Logos, which dwelt in the man.) Likewise, as I previously mentioned, there had also been a waxing and waning of sorts between iconophiles and iconoclasts since the earliest days of the Church, and this clash was finally to come to a head under Leo’s reign. As a result of all of these influences and pressures, in 726 Leo III issued an edict that restricted the use of icons in Christian places of worship.

This restriction quickly developed into a widespread campaign to destroy these supposed idolatrous images, and sadly the icons in many church apses and walls were covered by whitewashing. The controversy quickly became heated when the great image of Christ above the main entrance gate to Constantinople was taken down and destroyed. Orthodox Christians rightfully viewed this as an assault on Christ Himself. Just as when someone burns the US flag, the image itself is not what is being attacked, but what it represents. During this incident, we see how very different the Christians of that era are to our own. A group of tenacious and pious women, offended by this assault, physically tried to stop the soldier climbing up the ladder to the icon above the city gate. They arose from the crowd and made their way past the guards and ended up knocking over the ladder, which led to the soldier’s demise. In short, these women were not going to stand for the image of their Lord being desecrated before them.

The women were slain immediately on the spot by the emperor’s soldiers with the exception of the alleged ringleader, St. Theodosia, who is now honored among our Saints. She received more cruel punishments. She was dragged off through the streets, tortured, humiliated and later executed. Riots broke out in the city, and one of the great opponents to the iconoclasts Saint Germanus the upstanding patriarch of Constantinople appealed to Pope Gregory II to condemn this outrageous action. Pope Gregory II responded quickly to the dire situation and commanded Leo to stop meddling in the affairs of the Church. This is a problem that has always plagued the Eastern Church. Church and state never seemed to able to properly define their boundaries in Byzantium. Leo responded and commanded the Pope to convene a general council to address the issue of idol worship. Gregory in return chastised him, telling him that no council was needed and that there was no heresy involved in the proper veneration of the sacred images. Of course, as with most heretics, Leo paid no heed to the Pope’s words and instead escalated the war upon the monasteries, which were now one of the fiercest opponents to his heretical effort. Monks were murdered, tortured, and their sacred images desecrated and destroyed. The vigilant Patriarch Germanus who opposed Leo and appealed to the Pope was eventually banished as a traitor, but he always remained firm in his orthodox stance. While things were heating up in the East, this tragedy was thankfully something the Western Church did not have to endure. Things remained relatively quiet in the West where they largely ignored the controversy and the heretical Eastern emperor’s wishes.

In 741 emperor Leo died and there was an uprising to overthrow his son Constantine V. Anastasius, the bishop who replaced Germanus saw an opportunity and now turned on the iconoclasts and sought to restore the use of sacred images to Constantinople. The uprising was short-lived however when Constantine’s army marched upon the city and then had Anastasius flogged, blinded and driven into the streets, until he finally gave in to accepting the heresy. Blinding was a favorite punishment for the Byzantines. Every punishment in the history books by the Byzantines seem to read, “he was tortured, blinded and exiled.” Anastasius eventually died in 754, a crippled and broken man. Being that the Pope did not convene the council that his father had demanded, Constantine decided to call his own council. He gathered like-minded heretics from around the known world to officially condemn the use of sacred images. They held what was later known as “the robber council” and published their false anathemas against the iconophiles of the Church.

Constantine V then escalated the persecutions against the monastics who opposed his “council”. One head abbess was taken and tortured by having burning icons poured over her head. Constantine and his heretical clergy had nuns and monks marched into the hippodrome and humiliated, and they were forced to break their vows and marry. The priest-monk, Saint Stephen the Younger took many persecuted monks into his monastery. He out-rightly rebelled against the emperor and his alleged council and was imprisoned. Finally, a group of soldiers riled up a mob of iconoclasts and he was brutally dragged through the streets of the city, clubbed, stoned and finally expired after his brains were literally beaten from his skull. The monastics certainly took a beating, and a Byzantine historian writes, “...monastic property was confiscated and monastic buildings were turned over for military use.” Despite these harsh persecutions, the iconodules did not give up.

There many were many more great martyrs who stood up to the iconoclasts such as Peter the monk who was murdered after refusing to trample on an icon. Andrew of Crete heroically left his post as archbishop, set sail from Crete and came to Constantinople to personally address the emperor. He withstood Constantine V boldly to his face, condemned his maniacal, cruel actions and denounced his heresy. Constantine got so enraged at him that he had Saint Andrew arrested, tortured, killed and then thrown into a pit where common criminals were disposed. Saint Andrew is hailed as one of the great heroes of the iconoclastic controversy.

There is an unexpected hero of sorts, of our story, Empress Irene who was the wife of Leo IV the son and successor of Constantine V, and now who’s son, Constantine VI, only 9 years old was set to take the place of his father Leo IV. Being that he was of young age, his mother Irene became co-ruler. It was Empress Irene (787) who now sought to restore the use of sacred images in the East. In order to do this, however, she needed complete control of the government. If you know anything about the Byzantines, there was no shortage of drama, intrigue and hatched plots among their 1000 plus year existence. Irene had a problem, there were several rivals for the throne who had been waiting for her husband to die, so they could take advantage of the supposed weak empress. They certainly underestimated her tenacity and intelligence. Can you guess what clever device would she use to neutralize her and her son’s rivals? You guessed it, she had these rivals blinded so she would not have to worry about being interfered with. Yes, even heroes have their flaws. As Irene maneuvered key loyalists in place, she was able to secure her spot as empress. Her reign, however, would later become a problem when her son came of age. There were probably political motives of course, but Irene proved to be an asset for the orthodox Christians in the case of the iconoclastic crisis. She used any and all means to restore the sacred image. Furthermore, she also initiated an effort to have a legitimate ecumenical council called, to counter the earlier robber council.

During this period we see great Saints such as Saint John of Damascus, among many other valiant men and women, continuing in the war against the iconoclasts. Due to their efforts as well as a sympathetic empress, a general council was soon called. An effort was first made to convene at Constantinople but was thwarted by troops who were iconoclastic sympathizers. Irene underestimated the local army’s loyalty to the iconoclasts. The determined empress would not be deterred and slowly disbanded the local army and replaced it with soldiers who were loyal to her. The entire Church finally spoke in an official capacity at Nicea in 787 when the legitimate seventh Ecumenical Council was finally convened and the heresy was vigorously condemned by a series of anathemas. The Pope had at least 2 representatives present at the Council along with over 350 bishops from the known world as well as the Eastern Patriarch of Constantinople.

Although the controversy subsided after the Council, a resurgence of iconoclasm began again 27 years later due to remaining sympathizers again gaining a foothold in the government. More persecutions came and the renowned iconographer of the time Lazaros was brought before the high court where his hands were cauterized. This did not stop him, he also withstood them to the face and continued to paint icons with his scarred hands. Others were brought before the court and had inscriptions carved onto their foreheads identifying them falsely as heretics. A second wave of heroes arose such as Saint Ioanikios, Saint Theodore the Studite, and the great patriarch Nicephorous, who stood firmly against the icon smashers. Nicephorous the archbishop, too like Germanus years before him under Leo III, was eventually banished across the Bosphorous. Likewise, he never ceased to vigorously oppose the heretics.

The controversy finally came to an end due to another valiant woman, the empress Theodora. Due to her sympathies and influence, on the 11th of March, 843, fifty-five years after the seventh Ecumenical Council, and 116 years after the iconoclastic heresy began, a large procession of clergy and laity with icons in hand, put the iconoclastic controversy to end in the glorious Hagia Sophia. The kontakion (Byzantine hymn) sung during this procession sums up the Church’s teaching well, "No one could describe the Word of the Father; but when He took flesh from you, O Theotokos, He accepted to be described, and restored the fallen image to its former state by uniting it to divine beauty. We confess and proclaim our salvation in word and images."

Theological Defense

Now I want to turn briefly to the theological explanations that came out of this controversy, and then I will proceed to examine the sacred icon itself, and the theology that separates them from other forms of artistic expression. Perhaps the most notable Saint and theologian to arise out of this era was Saint John Damascene. He wrote an infamous apologia for the use of sacred images. I think it is worth quoting a small portion of his document to further explain the proper teaching of the Old Testament ban on graven images, and how it relates to the Church.

“Now adversaries say: God's commands to Moses the law-giver were, "Thou shalt adore shalt worship him the Lord thy God, and thou alone, and thou shalt not make to thyself a graven thing that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath."

They err truly, not knowing the Scriptures, for the letter kills whilst the spirit quickens--not finding in the letter the hidden meaning...

You see the one thing to be aimed at is not to adore a created thing more than the Creator, nor to give the worship of latreia except to Him alone. By worship, consequently, He always understands the worship of latreia. For, again, He says: "Thou shalt not have strange gods other than Me. Thou shalt not make to thyself a graven thing, nor any similitude. Thou shalt not adore them, and thou shalt not serve them, for I am the Lord thy God." (Deut. 5.7-9) And again, "Overthrow their altars, and break down their statues; burn their groves with fire, and break their idols in pieces. For thou shalt not adore a strange god." (Deut. 12.3) And a little further on: "Thou shalt not make to thyself gods of metal." (Ex. 34.17)

You see that He forbids image-making on account of idolatry, and that it is impossible to make an image of the immeasurable, uncircumscribed, invisible God....These injunctions were given to the Jews on account of their proneness to idolatry. Now we, on the contrary, are no longer in leading strings. Speaking theologically, it is given to us to avoid superstitious error, to be with God in the knowledge of the truth, to worship God alone, to enjoy the fulness of His knowledge. We have passed the stage of infancy, and reached the perfection of manhood. We receive our habit of mind from God, and know what may be imaged and what may not...

It is clear that when you contemplate God, who is a pure spirit, becoming man for your sake, you will be able to clothe Him with the human form. When the Invisible One becomes visible to flesh, you may then draw a likeness of His [9] form. When He who is a pure spirit, without form or limit, immeasurable in the boundlessness of His own nature, existing as God, takes upon Himself the form of a servant in substance and in stature, and a body of flesh, then you may draw His likeness, and show it to anyone willing to contemplate it. Depict His ineffable condescension, His virginal birth, His baptism in the Jordan, His transfiguration on Thabor, His all-powerful sufferings, His death and miracles, the proofs of His Godhead, the deeds which He worked in the flesh through divine power, His saving Cross, His Sepulchre, and resurrection, and ascent into heaven. Give to it all the endurance of engraving and colour. Have no fear or anxiety; worship is not all of the same kind.”

The incarnation is the binding agent that grafts the sacred image into the body of the Church. Here Saint John amply explains the orthodox Christian understanding of these Old Testament texts. I think it is also important to briefly cover some of the statements made by the seventh Ecumenical Council, which formally upheld the traditional teaching of the Church’s use of sacred images. At the end of the first session of the Seventh Ecumenical Council, John, the most reverend bishop and legate of the Eastern high priests said: “This heresy is the worst of all heresies. Woe to the iconoclasts! It is the worst of heresies, as it subverts the incarnation (οἰκονομίαν) of our Savior.”

In Session 1 the Council issued the following anathemas which were proclaimed by bishops reconciling themselves to the Church.

Anathema to the calumniators of the Christians, that is to the image breakers.

Anathema to those who apply the words of Holy Scripture which were spoken against idols, to the venerable images.

Anathema to those who do not salute the holy and venerable images.

Anathema to those who say that Christians have recourse to the images as to gods.

Anathema to those who call the sacred images idols.

Anathema to those who knowingly communicate with those who revile and dishonour the venerable images.

Anathema to those who say that another than Christ our Lord hath delivered us from idols.

Anathema to those who spurn the teachings of the holy Fathers and the tradition of the Catholic Church, taking as a pretext and making their own the arguments of Arius, Nestorius, Eutyches, and Dioscorus, that unless we were evidently taught by the Old and New Testaments, we should not follow the teachings of the holy Fathers and of the holy Ecumenical Synods, and the tradition of the Catholic Church.

Anathema to those who dare to say that the Catholic Church hath at any time sanctioned idols.

Anathema to those who say that the making of images is a diabolical invention and not a tradition of our holy Fathers.

This is my confession [of faith] and to these propositions I give my assent. And I pronounce this with my whole heart, and soul, and mind.

Furthermore, the Council proclaimed,

“We, therefore, following the royal pathway and the divinely inspired authority of our Holy Fathers and the traditions of the Catholic Church (for, as we all know, the Holy Spirit indwells her), define with all certitude and accuracy that just as the figure of the precious and life-giving Cross, so also the venerable and holy images, as well in painting and mosaic as of other fit materials, should be set forth in the holy churches of God, and on the sacred vessels and on the vestments and on hangings and in pictures both in houses and by the wayside, to wit, the figure of our Lord God and Saviour Jesus Christ, of our spotless Lady, the Mother of God, of the honourable Angels, of all Saints and of all pious people. For by so much more frequently as they are seen in artistic representation, by so much more readily are men lifted up to the memory of their prototypes, and to a longing after them; and to these should be given due salutation and honourable reverence (ἀσπασμὸν καὶ τιμητικὴν προσκύνησιν), not indeed that true worship of faith (λατρείαν) which pertains alone to the divine nature; but to these, as to the figure of the precious and life-giving Cross and to the Book of the Gospels and to the other holy objects, incense and lights may be offered according to ancient pious custom. For the honour which is paid to the image passes on to that which the image represents, and he who reveres the image reveres in it the subject represented. For thus the teaching of our holy Fathers, that is the tradition of the Catholic Church, which from one end of the earth to the other hath received the Gospel, is strengthened. Thus we follow Paul, who spake in Christ, and the whole divine Apostolic company and the holy Fathers, holding fast the traditions which we have received.”

I could spend much more time on this most important Ecumenical Council. In many ways, this Council is more important to us today than the Second Vatican Council since we have had more than 50 years of a silent iconoclasm destroying the Church from within, with little to no resistance. I think it would be safe to say that the great Saints of this past time period would be astonished at the laxity in which we have allowed the sacred image to be desacralized in our Church today. The sacred image instills in us a love for God and His Saints. There is a much-needed devotion for the icon in our sad times of unbelief. In the end, it comes down to us the faithful, like you and I, who must resurrect the devotion and veneration of the icons in the West, of which these most valiant Saints sacrificed, suffered and died to pass on to us. Will we let their sacrifice go unheralded in our time?

The Theology of the Icon

Renown iconographer and iconographic historian Aiden Hart writes, “Perhaps the most essential aspect of any sacred art is that it mediates between a higher divine realm, and our realm.”

I will now briefly cover how an icon is composed and the theological underpinnings which give the icon its unique Christological locus. Everything pertaining to the icon revolves around Jesus Christ. Saint Athanasius once said, “He became man in order that we might become God.” This central theme of deification, or commonly called theosis in Greek, is the heart and soul of the icon. It leads man to an encounter with God through meditation, in which God, through His grace transforms him. In other words, we should all be climbing the ladder of divine ascent, and the icon helps us to do just that. Father Daniel Montgomery writes, “An icon seeks to make visible the borderline between heaven and earth. Its subject matter may be “in” this world but not “of” this world.” I hope that the closing part of this essay will inspire you to make the icon a more integral part of your personal devotion and prayer life.

Metropolitan Hilarion spoke rightly when he said, “The icon’s purpose is liturgical; it is an integral part of liturgical space, which is the church, and an indispensable participant in divine services... Certainly, every Christian has the right to hang an icon at home, but he has this right only in so far as his home is a continuation of the church and his life a continuation of the liturgy... The icon participates in the liturgy along with the Gospel and the other sacred objects. In the tradition of the Orthodox Church, the Gospel is not only a book for reading but also a liturgically revered object: during the liturgy the Gospel is solemnly brought out for the faithful to kiss. In a similar way, the icon as “Gospel in color” is an object not only to be contemplated but also to be venerated with prayer.”

Catholics along with the other apostolic Churches (Orthodox Churches) give reverence to the Gospels and Sacred Images during our liturgical worship. We should understand that the veneration we give to the Gospels, the Saint’s relics and the Holy Images is not the same as the worship we give to God alone, which is known by theological scholars as latria. The veneration and bowing or prostrating before the icon is known as proskynesis. As Catholics, we have a special honor that we give to the Saints and the Mother of God. Although the type of “worship” that we give the Saints and Almighty God is certainly different, God still remains the central focus of devotion. Even when the Christian engages in the tradition of proskynesis before an icon, he or she is really honoring the work of God’s grace in man. In our Latin theological Tradition, we hold three modes of worship: latria which is the worship due to God alone. Hyper-dulia which is the high devotion or veneration to the Mother of God, for she is, “More honorable than the cherubim and truly more glorious than the seraphim” and finally, we have dulia or the common veneration of the Saints.

Iconographic Setting

Most icons in churches are traditionally either grafted as frescoes or mosaics onto the walls, are on panels attached to walls, or are on panels installed into an iconostasis which separates the sanctuary from the nave. In the Eastern Church, the icon of the particular Church Feast of the season, or an icon of Christ or the Theotokos is kept in the front of the church in front of the sanctuary for veneration. In the West, this type of icon veneration is also practiced, although the icons are usually near the entrances of the church, and they did not usually correspond to a particular liturgical season. This Western practice of icon veneration is almost extinct in American Catholicism. However, if you go to Rome for example, this practice is still alive and well. In the West, usually, only an altar rail or rood screen was used to separate the nave from the sanctuary, while in the Eastern Church the separation developed to bring the sacred image to a place of prominence before the worshipper.

The iconostasis of the East began with a low wall containing one row of icons, and it developed quickly to contain more images. The pinnacle of iconostasis construction is found in the Russian tradition where the iconostasis can span from floor to ceiling containing many rows of icons. This engages the worshipper with images of Christ and His Saints, putting before him or her in sacred image what is actually happening in the liturgy. It is nothing short of the kingdom of heaven brought to mankind as described in Revelation 21:1-3, “Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth...And I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God... and I heard a loud voice from the throne saying: “Behold, the dwelling of God is with men.” There is a proper order in which the icons are traditionally placed on the iconostasis. The royal doors at the center contain the four evangelists and a depiction of the Annunciation. Christ and the Theotokos flank the royal doors, the archangels flank Christ and the Theotokos, and the Saints, and usually the patron Saints of the Church flank the Archangels. Above, there are usually depictions of the Feast days of the Church along with other Saints.

Although the Western Church did not develop in the same way as the Eastern Church did in regard to iconography, it is not accurate to say that icons are an exclusive product of the Eastern Church. This is a mistake made by many today who ignorantly attribute iconographic images as a product of the Eastern Church. Both the East and West share a mutual love and heritage for the sacred image. In fact, iconographic scholar and historian Hans Belting says that the original concept of the icon is best understood in light of the churches of Rome. Note, I did not say the icon is a product of Rome. In the Roman churches, however, we see the same setting, in which most of the early iconography was displayed, which was on the walls or apse of the church rather than what we see with the development of the iconostasis in the East.

There are many splendid Western churches such as Saint Mark’s in Venice, San Vitale in Ravenna, Santa Maria Maggiore and Santa Maria en Trastevere in Rome which have their interior walls, apses, and domes covered with mosaic iconography. Although most Western Churches do not make use of an iconostasis as such, the apse and walls on each side of the apse facing the nave, have iconographic depictions and engage the worshipper to the liturgical setting of the West. This setting for the icon is earlier than that which developed in the East with the iconostasis. I personally consider Saint Mark’s in Venice to be the pinnacle of Western Iconography. I had the wonderful privilege of celebrating Easter Vigil in 2007 there, and it was nothing short of remarkable. The West may have indeed kept this traditional Roman use of the icon, and it may have even developed further had the Renaissance not interfered. The Renaissance in the West marks a departure away from traditional icon depiction in the Western Church.

The Separation of Sacred Art and Religious Art

The beautiful and inspiring work of Giotto di Bondone can be viewed as the dividing line between the more purely theological image of the icon, and the more secular artistic styles that would soon follow him. We begin to observe movement in Giotto’s image, which had been traditionally absent from the icon. The following renaissance painters broke completely from the traditional form of producing sacred images, in favor of more realistic depictions. The late Catholic priest and iconographer Monsignor Anthony La Femina calls this later art “religious art” rather than “sacred art” being that it depicts only religious events rather than the more theological composition which the icon depicts, aiming at devotion rather than events. The later efforts at depicting a more “realistic” image, was a misguided one when looked at in the context of liturgical and devotional use since more corporeal aspects of religion began to dominate over its eternal mystical realities. The more important spiritual aspect of the sacred image was eventually replaced with the corporeal.

Although religious art can certainly be beautiful, inspiring and have its place in Catholic culture, it should certainly not have completely taken the place of the sacred image or icon. Here my criticism is not aimed at the quality of the Renaissance art itself but is aimed at the deficiency of its ability to inspire meditation beyond itself. This same secular movement would come into play theologically in the West as well when secular humanism became to take hold of many in the Church, eventually playing a part in the later Protestant rebellion.

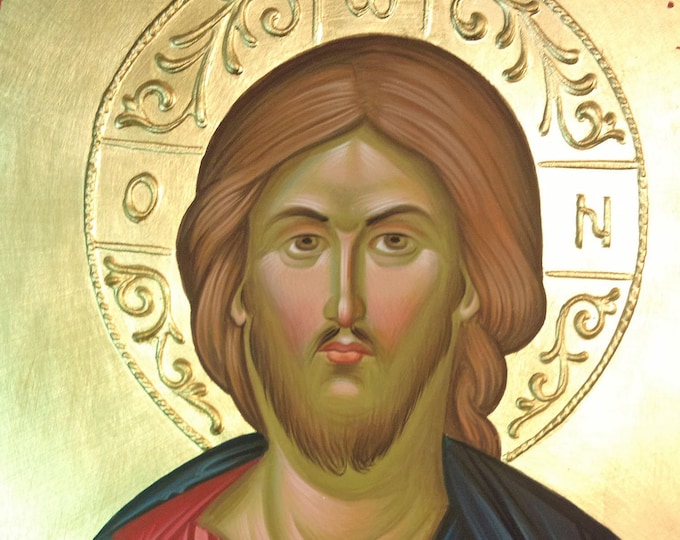

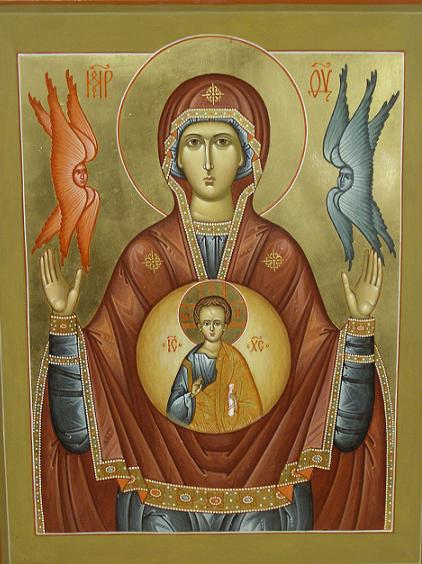

If we examine the traditional icon, we do not see an image of an exact representation of a Saint, the Theotokos or even Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, as they were when they walked the earth. Nor do we see an attempt at a purely realistic depiction of a Biblical event. The Biblical depictions are not rendered in motion but as eternal events or states. The icon does not show the Saint in motion but intends to convey the glorified Saint, who is fully deified by the grace of God. Hence, you do not see an attempt at a three-dimensional depiction. Father Daniel Montgomery notes, “There is no depth to the picture, and that is just what disturbs us about it at first glance. The picture seems primitive. A closer study reveals, however, that the picture is often exceedingly complex. The flatness, for example, is sometimes achieved by drawing perspective in reverse. The artist expects us not to look at his picture, but through it.”

Notice that there are no vanishing points which give the impression that you are seeing the image from front to back. Again I refer to Metropolitan Hilarion for further explanation, “The icon of a saint shows not so much a process as a result, not so much a way as a destination point, not so much a movement towards a goal but as a goal in itself. In an icon we see someone who does not struggle with the passions but has overcome them, who does not seek the Heavenly Kingdom but has already reached it.” The icon also illustrates heavenly traits unique to different Saints and there are also traditional iconographic models for each Saint which makes them recognizable. For example, you can always recognize Saint John Chrysostom due to his slightly enlarged forehead, representing his great wisdom and holiness. The icon opens the door to the Saint, letting us know that Christ is the God of the living and that His Saints are interceding for us as they stand before Him in heaven.

The Unique Theological Setting of Icons

For those who are not familiar with the icon, again it is important to understand that the icon is not concerned with a perfectly “realistic” depiction of a Saint in his earthly form or setting. The iconographic scholar Constantine Cavarnos stresses this point, “Iconography represents persons who have been regenerated into eternity.” Likewise, Christ is depicted as an eternal figure, with both His divine and human natures, rather than with only His human nature, which would be stressed in later Western religious art. We can see in an icon of the crucifixion, that the icon retains a focus on not only the crucifixion event but also on Christ as the eternal Son of God. The viewer is not distracted but drawn into contemplation. The crucifixion event is not one of movement, but of an eternal nature, leading one beyond the image to the eternal Sacrifice. Metropolitan Hilarion says, “The Byzantine icon is not merely an image of the man Jesus but precisely God become man. This is what distinguishes the Orthodox icon from Renaissance religious art which represents Christ “humanized”.

The later Western religious depiction of the crucifixion such as Tintoretto's striking depiction in Venice, although certainly bold and beautiful, somewhat obscures the divine realities, and therefore does not draw one as easily into contemplation. Instead, it pulls the viewer to and fro examining the many figures at the foot of the cross and other intriguing illustrations. Alternatively, as we meditate on the warm, glowing, and radiant icon, the idea of both the human and divine natures of Christ come to mind, and we begin to see ourselves in the process of deification. The icon does not distract but leads one beyond itself. As Catholics, we struggle to achieve, by the grace of God, the pure state in which we will be glorified in heaven. When we enter a church to worship the one true God, to receive His Body and Blood, we are essentially entering into eternity, and when we see the sacred images before us, we become more aware of this elusive, yet extremely important reality. So the icon mirrors the priority of the spiritual over the corporeal.

Bishop Auxentios writes, “...the spiritual and the physical exist in a hierarchical relationship in man's restored state, the spiritual enjoying the ascendancy. Ideally, then, the body serves, and does not hinder, the spirit, as the latter worships, prays, psalmodizes, and performs good works or acts of asceticism and self-denial.” Therefore, the icon also follows this theological model by bringing asceticism to the forefront of the viewer’s mind.

This central role of God deifying us does not stop when we leave the church doors, therefore it is important for the sacred images to be present in our homes. In the West, we are more familiar with having statues or forms of religious art in our homes rather than icons to help us in our private devotions. Many of them are indeed beautiful, and I have many myself. Although I believe that statues retain the attributes of the sacred image in a three-dimensional presentation or form, most Eastern Orthodox scholars would disagree with me on this point. I do think they sometimes still tend to lack the mystical element of the icon, but nonetheless, they usually present the Saint in a glorified state rather than an earthly one and thus I would argue that they qualify truly as sacred art. Likewise, I would argue that the stained glass tradition of the West also qualifies as sacred art for the same reason. I consider them icons made of glass. As far as religious art goes, they make great decoration, they can help teach us about past religious events, and they can certainly lead us to ponder our faith. In my opinion, however, they are certainly no substitute for the sacred icon. They simply lack the mystical element to draw man beyond the image itself.

Bishop Auxentios illustrates the importance of icons in the traditional Russian Christian household, which I think is useful to us as Western Catholics. “In Orthodox homes, the eastern corner of a centrally located room is always dedicated to the display of icons. There are usually many such icons on display (twenty-five to thirty icons would constitute a conservative average), and this "icon corner" always features at least one vigil lamp hanging before it, religiously and perpetually kept burning by the members of the household or, in the event of their absence, by someone hired or appointed for this task.” Now obviously I am not implying that you should leave candles or lamps burning day and night, or that you go out and hire yourself an icon keeper to keep the vigil lamps burning 24/7. What I am stressing here is how important it is to maintain an iconic presence of God and His Saints in our homes.

Extreme perhaps? No more extreme than what the average American does weekly such as continuously viewing syndicated television programs or sporting events, overeating rich foods, spending lengthy amounts of time on the internet, putting themselves in immediate occasions of sin partying down at the local club, consuming massive amounts of alcohol or the many other forms of escapism many indulge in today. In other words, the things we are “extreme” about are the things we truly love. Where we spend our time, and what we spend our time doing, in essence, tells us what or whom we truly love. Although I have used an example here of how the Russians in the East venerate icons in their homes, we should not think that private veneration of icons is an Eastern phenomenon. In fact, historian Hans Belting explains that Christians in the early centuries in the West often carried relic boxes with icons on them when they went on pilgrimages to holy sites. Likewise, the use of small icons for personal devotion in the household was common. This is one devotional practice that urgently needs to be restored in the West.

Theological Depiction Incarnate

There are five core characteristics of an icon:

1. The icon first leads us into prayer.

2. The icon gives us a portrait of holiness as well as a historical incarnational truth of the person depicted.

3. The icon gives us a theological truth, which of course varies depending on the event, person or persons depicted.

4. The icon has didactic meaning, one which gives us a religious or moral teaching.

5. The icon contains an anagogic meaning, which unites the earthly with the mystical heavenly realm, and the afterlife.

If we look even closer at the icon we can see what separates it further in its composition from secular forms of art. Certainly, the methods in which the icon has been produced have developed with time. The icon has been traditionally made with mediums such as encaustic wax, plaster, tile, and egg tempera. The earliest sacred images were certainly simple productions made with pigments from the earth in the form of frescos, and soon after mosaic tiles. Likewise, today’s traditional iconography, although more theologically advanced, maintains a similar practice that makes use of earth pigments, mixed with egg, creating a medium known as egg-tempera.

There are three characteristics of the iconographer as he engages in painting (writing) an icon. They are, ‘theory’, ‘practice’ and ‘contemplation’.

1. Theory is the vast amount of time the iconographer spends in prayer, in researching, studying and observing the icon and the iconographic process.

2. Practice is the actual icon writing itself, in which the iconographer uses prayer, a physical medium, a theological framework, and a recognizable iconographic model to write the icon.

3. Contemplation is the important internalization of writing the icon, which bonds the person with the eternal Godhead through the icon writing process. This is also known as theoria. In a sense, the icon speaks to the iconographer during the process of its creation. In essence, the icon itself becomes a prayer.

If we examine a panel icon, we see that it is painted where light is brought out from the darkness. Acrylic paints are now being used by some iconographers today, but even when using this medium, the same process of applying the color from dark to light is the same. The image begins with preparing a board with gesso, a mixture of plaster and glue. It is sanded smooth and then an image is either drawn or transferred onto the board. After this is done the image is incised or scribed into the board with a sharp object like a scribing tool. Once this has been done the painting can begin. The background and halo are done first, usually with a clay base, which will be covered in gold leaf. Then a color medium is used to paint the clothing or other objects.

There are several layers of highlighting done, and some schools separate them with veils of a thin medium. The highlighting brings the image out of the darkness into the light. As the process continues, we begin to see the grace of God radiating through the icon. All of these steps have a theological meaning, which gives the image a unique bond with both the iconographer and all those who will meditate on it. Through the many steps of writing the icon, it slowly becomes a window, or more accurately, a doorway to heaven.

We traditionally say that the iconographer does not “paint” an icon, but “writes” it, noting the difference in how the icon is created compared to other art. It is written in much of the same way as Scripture is written, in other words, it is the gospel in image. Just as the technique is of crucial importance to the creation of an icon, so is the choice of pigments. There are general principles in choosing what colors are used on an icon, but it must be stressed that there have been various schools of iconography which have varied in practice, separated by time and geographical area. So, as a general rule, we have the following color explanations.

Gold symbolizes God’s divine light, grace or the splendor of the celestial kingdom. Hence we see the background and halos in gold. Notice how the halo is different from that of later Western art.

Purple symbolizes royalty, we see Christ and some Saints in purple.

Red can depict the passion of God’s love and divinity. It is also used to depict the blood of martyrdom as is often seen in the icons of the Saints who were martyred.

Green may also be used to depict martyrdom in icons.

White is the symbol of the heavenly realm and is also the color of holiness and cleanliness. Sometimes we see Christ in white such as in the icon of the Descent Into Hell.

Blue is a symbol of eternity or heavenly participation. In some instances it also depicts humanity. For example, in many icons, you see the Theotokos often wearing blue with red on the outside, showing her humanity covered by divinity. Christ is often shown the opposite, wearing red on the inside and blue on the outside symbolizing His divinity clothed with His humanity.

Brown is used to depict the earthly realm or human nature. It also depicts poverty and many monks are depicted wearing brown.

Black usually denotes death or eternal darkness. Demons are always depicted black in iconography.

There are six traditional categories of icons.

1. The Lord Jesus Christ, or Christ the Savior. Christ is depicted in many forms, such as the Pantokrator or the Teacher.

2. The Theotokos, or Mother of God, often called the All-Holy One or the Panagia. Likewise, there are many forms in which she is depicted, such as The Guide, Tender Mercy, or the Oranta. (explain 3 stars- virginity)

3. We have the angels, such as Saint Michael or Saint Gabriel.

4. We have the Feasts of the Church such as the Annunciation, the Descent into Hell or the Epiphany.

5. Then we have the many Saints of the Church of which the most famous include Saint John Chrysostom, Saint Nicholas and Saint Gregory the Great.

6. Finally, we have didactic icons that are aimed at specific teachings. We have the icons of the Old Testament for example such as Abraham and Isaac, The Old Testament Trinity, or the Three Holy Youths in the Furnace.

Summary

It would be a mistake before I close this essay not to recap on how the sacred image helps us to grow in the love of God. I would like to expound on a few thoughts with Aiden Hart’s perspective on some spiritual aspects of the icon.

Sacred art participates in what it represents- Thus the icon helps us to realize the eternal world we enter into when we enter a church. The building, the art and everything material is consecrated for the purpose of worshipping the one true God.

Sacred art aids repentance- The way the icon depicts divine realities inspires in us to turn towards the light of grace which is depicted in them. The icon also helps us to remove ourselves from the egocentric world we find ourselves regularly immersed in. I would add, that we need the sacred image, to go beyond ourselves and contemplate the eternal.

Sacred art is liturgical- When we enter the church we see sacred images before us. They help us to engage in the liturgical functions more fully. Likewise the sacred images should be venerated, kissed or processed with. We see the procession in the West most frequently with statues of The Blessed Mother, on the Feast of the Assumption for example, while in the East a panel icon is frequently processed with during a Feast. When we honor the icons in our homes, we are actually extending what happens in the liturgy into our homes.

All three of these attributes of the sacred image bring us to love God more fully. The sacred image brings before our eyes the most beautiful divine realities of the incarnation of Christ, and thus our deification and salvation.

I will leave you now with a few thoughts about the icon, and what it means for us as Catholics today. The great iconographer Leonid Ouspensky writes, “The fundamental principle of this art is a pictorial expression of the teaching of the Church, by representing concrete events of sacred History and indicating their inner meaning. The art is intended not to reflect on the problems of life but to answer them, and thus, from its very inception, is a vehicle of the Gospel teaching.” Furthermore, the icon is not merely an optional type of devotion of our Christian faith. It is an integral part of our spiritual life and cannot be dispensed with without severe spiritual depravity. Ouspensky continues, “the doctrine relating to the image is not something separate, not an appendix, but follows naturally from the doctrine of salvation, of which it is an inalienable part.”

I propose that along with the loss of many of our traditional practices in the Catholic Church, the loss of the sacred image has been one of the most devastating in our era. The Eastern Church won their battle over the iconoclasts and have since developed their own iconic tradition which continues vibrantly today. In the West, our war has yet to be waged against our present-day iconoclastic movement. The bishops who facilitate this desacralization do not have to outrightly come out and formally condemn the use of icons in word as the heretics did in the eighth century, but their actions are very similar. Many bishops and their minions have marched into churches, whitewashed the images, jackhammered out altars adorned with sacred images and discarded them like yesterday’s garbage. The sacred image has also been prohibited from being placed into new churches, and instead have been replaced with deformed, profane images.

The loss of the sacred image in Western Catholic culture has been detrimental to the Church and society. This decline has come alongside modernist theological errors that have crept into the Church, coming to its full iconoclastic pinnacle over the last 50 to 60 years. The era of modernism following the Second Vatican Council has now almost done away with the sacred image in our Western Catholic worship, both in liturgical and in private devotion. It is not acceptable that many of our Catholic churches today can’t be distinguished from a secular auditorium or business park. Silence should no longer be tolerated when it comes to the profanation of sacred images and the ongoing onslaught of church wreck-ovations today. We must insist on the restoration of our Western sacred art tradition which I believe includes the sacred icon, the three-dimensional icon of the statue, and the glass form of the icon in stained glass.

We have obviously lost much of our Roman iconographic heritage. It is up to us to revive the sacred image by introducing them back into our Western Catholic tradition. They must be a part of our public and private devotion. We can each choose to reintroduce this devotional practice starting in our homes and pass it on to our children. May we have the courage and fortitude to stand up today like those many Saints who came before us, who sacrificed everything they had to save the sacred image.

If we listen closely we can still hear the inspiring chants of the Byzantine faithful as they happily processed through the streets of Constantinople lovingly cradling their icons in their arms glorifying God and His Saints.

They sang something like the Troparion which is sung in the Eastern Church in veneration of Saint Nicephoros of Constantinople, to whom we should all ask for intercession so that we may win our war in the West against the wretched iconoclasts.

Your inspired confession gained victory for the Church, O holy Hierarch Nicephorus.

You suffered unjust exile through reverence for the icon of God the Word.

O righteous Father, Pray to Christ our God to grant us his great mercy!

Bibliography

Andrejev, Vladislav. Theoria. New York, NY. Prosopon School of Iconography. DVD

Angold, Michael. Byzantium: The Bridge From Aniquity to the Middle Ages. New York,NY: St Martin’s Press 2001. Print.

Beckwith, John. Early Christian and Byzantine Art. Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin, 1979. Print.

Belting, Hans. Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1994. Print.

Bigham, Stephane. Early Christian Attitudes toward Images. Rollingsford, NH: Orthodox Research Institute, 2004. Print.

Hart, Aidan. "The Sacred in Art and Architecture." N.p., n.d. Web

.

Herrin, Judith. Women in Purple: Rulers of Medieval Byzantium. London,UK: Weidenfeld & Nicholson (Princeton) 2001. Print

Hilarion, Alfeyev. "Theology of Icon in the Orthodox Church." St Vladimir's Seminary. 5 Feb. 2011. Lecture.

Montgomery, Daniel. Icons Differ From All Other Art In Its Mysticism. Publication of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America 1958

John, and David Anderson. On the Divine Images: Three Apologies against Those Who Attack the Divine Images. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary, 1980. Print.

Kontoglou, Photes, and Constantine Cavarnos. Byzantine Sacred Art: Selected Writings of the Contemporary Greek Icon Painter Fotis Kontoglous on the Sacred Arts According to the Tradition of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Belmont, Mass., U.S.A.: Institute for Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 1985. Print.

Ouspensky, Leonide, and Leonide Ouspensky. Theology of the Icon. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary, 1992. Print.

Ouspensky, Leonide, and Vladimir Lossky. The Meaning of Icons. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary, 1982. Print.

Quenot, Michel. The Icon: Window on the Kingdom. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary, 1991. Print.

Safran, Linda. Heaven on Earth: Art and the Church in Byzantium. University Park, Penn.: Pennsylvania State UP, 1998. Print.

Talbot, Alice-Mary Maffry. Byzantine Defenders of Images: Eight Saints' Lives in English Translation. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1998. Print.

By Matthew J. Bellisario O.P. 2012, 2013, 2020

The par excellence of all theologians, Saint Thomas Aquinas, wrote in his explanation of the sacred image the following, “There were three reasons for the introduction of the use of visual arts in the Church: first, for the instruction of the uneducated, who are taught by them as by books; second, that the mystery of the Incarnation and the examples of the saints be more firmly impressed on our memory by being daily represented before our eyes; and third, to enkindle devotion, which is more efficaciously evoked by what is seen than by what is heard.”

In 2012 I gave a lecture at my local parish in Sarasota, Florida concerning sacred images. I received a positive response from those who attended the lecture so after some thought I decided that it may make an informative blog article. I originally posted this lecture as a series of posts on my old blog Catholic Champion in 2013, which has since been retired. There are however several essays that with some editing I think are worthy of passing over to this new blog. This is one of them. The sacred image, and the devotion that surrounds it is dear to my heart. I hope that this lengthy revised essay may increase your love of God and His Saints through an increased veneration of the sacred image.

|

“And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us.” John 1:14

If we were to be transported back almost 1200 years, to the 11th of March, 843 to the glorious crown jewel of Christendom at the time, Constantinople, we would be witnessing one of the eye-catching and jubilant processions to ever be held in the city. We would see the stunning Empress Theodora, along with the Archbishop, his priests, and all the faithful chanting as they passed through the streets of the city carrying icons to the grandest of all churches in Christendom, the Byzantine church, the Hagia Sophia, known as ‘the church of Holy Wisdom’. This would be where the Eastern Church would celebrate the triumph of Orthodoxy, that is, the victory over the iconoclasts who had plagued the Church of the East for over 100 years. As the people chanted their way into Justinian’s masterpiece, anathematizing the iconoclasts, they must have recollected the many men and women who had been tortured, exiled or even murdered to defend the sacred image. Many of us remember when we attended our first Latin Mass and how excited we were to see the Latin Mass arise from the ashes after 60 years of oppression. The Byzantines must have felt much the same, yet even more appreciative of their triumph, since it was one which had overcome by the blood of their brothers, sisters, and forefathers which now stained the soil of their streets and monasteries. A Byzantine scholar writes that the heroic virtue of the Saints of this period would fill several volumes of books. Why did the Christians of Constantinople fight so vehemently to retain the use of the icon, or sacred image? Hopefully, by the end of this essay, I will have provided some answers, and also have instilled in you the reader a spirit of reintroducing the veneration of sacred images in our time.

The Problem

There are certainly several reasons why such a topic is of great importance to us as Catholics today. With the dawn of this new iconoclasm in the Church of our age, it would be of little effort to prove that a new spirit of evangelization is needed in the realm of Sacred Imagery within the Western Church. Many of our once beautiful Catholic churches built by our forefathers have been openly desacralized, and many of their Sacred Images have either been destroyed or removed from these holy places of worship. Our modern iconoclastic crisis is not limited to the destruction of the older churches, but many of our new churches were constructed under a most heinous heretical enterprise. Our modern church architecture has declined far beyond even the barren whitewashed tombs born out of the iconoclastic mindset of the pretended “Reformers” such as Calvin of the sixteenth century. The primary aim of my essay is not only to condemn the errors of the iconoclasts of our age. This essay is to be first and foremost oriented towards the love of God, His Church, and His Saints, and to hopefully inspire you to develop a devotion to Christ and His Saints through the sacred image.

The Solution

If we are to understand the important role of the sacred image in our lives as Catholics, and if we are to prudently share the one true faith with others as the Church calls us to do, we must be armed fully with faith and reason. This means that we must put an effort into learning more about our faith, and putting what we learn into practice. Benedict XIV had just cause to write: "We declare that a great number of those who are condemned to eternal punishment suffer that everlasting calamity because of ignorance of those mysteries of faith which must be known and believed in order to be numbered among the elect." So my aim is also to give you more information about our Catholic faith, so you may be enriched and then enrich others in the Catholic faith. This essay is not by any means an in-depth analysis of this most theologically and historically complex subject. I have composed this essay to hopefully give you the tools to make the sacred image your own in your parish church and in your own home. Furthermore, I hope to demonstrate that we have not only a just cause to rebel against those who seek to eradicate the use of sacred images in our Church, but it is a duty. I hope that this written presentation will inspire you to live the Catholic faith in the midst of our own persecutions. At the end of this essay, I will list the many valuable sources I have used to write this so that you may obtain them for further study if you wish. It may come as a surprise that many of the sources I used are from Eastern Orthodox scholars rather than Catholic scholars. The simple reason being is that Catholic scholarship on this subject is embarrassingly limited. I hope that this will change in the future.

|

| The Incarnation |

It is always a good practice to meditate on the incarnation of Christ, to which the Sacred Image is so uniquely and intimately bound. It can be said that the icon is truly Christological and theological, and outside the dogmas and doctrines of the faith, they cannot be properly understood. Metropolitan Hilarion, the chairman of the Moscow Patriarchate’s Department for External Church Relations, and who is also one of the most relevant modern scholars concerning the icon, in his Feb 5th, 2011 lecture on the meaning of icons said, “The icon is closely bound up with dogma and is unthinkable outside its dogmatic context. Through artistic means, the icon communicates the essential doctrines of Christianity of the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation, salvation and human deification.” This is an important fact to keep in mind as you go through this essay. Sacred images, or icons as I will also refer to them throughout this paper, are not like any other art in the world, being that they are uniquely Christian, created not only to teach the Christian faith but to lead us more fully into living the Christian faith. They are more than depictions of past events, portraits, or mere decorations designed for our churches. The icons are windows or doorways to the eternal. They are the gospel of Jesus Christ in image.

Early History and Archeological Evidence

Our journey in tracing the use of the sacred image first leads us to the catacombs just outside of Rome. Here we have some of the earliest depictions of Christ frescoed on the walls underground where Christians had Masses for the dead who were buried there. The images of ‘Christ and the Samaritan Women’ and ‘Christ the Good Shepherd’ date back to the early third century. The image of Christ the Good Shepherd from the catacombs of St. Callixtus brings to mind the Gospel of John 10:14-15, “I am the good shepherd; and I know mine, and mine know me. As the Father knoweth me, and I know the Father: and I lay down my life for my sheep.” These images and others from the catacombs were once thought to be the only Christian images to exist from this period.